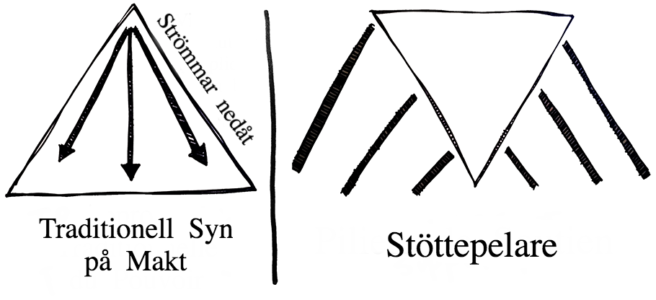

Traditional power is thought of as a pyramid, where power flows from the top downward. A janitor takes orders from a supervisor who takes orders from a district head, and so on — all the way up to a CEO or head of state at the very top of the pyramid. In that way of viewing power, social change happens when we either replace the people at the top (for example, regime change or voting) or are able to convince the top to change their ways (for example, educating them via a major public outcry).

But that’s not a grassroots way of viewing power. That leaves power in the hands of the oil executives and the rest of us begging for them to do the right thing. We need a new way of viewing the power.

The grassroots way views power as flowing upwards: this is the upside-down triangle.

In this way of viewing power, the oil executive or head of state is inherently unstable. Like an upside-down triangle, unjust power and authority is unstable and will fall. To prevent that, that rely on supports to keep them upright—we call them pillars of support.

For example, oil executives are dependent not only on their managers, but other pillars of support like the company’s stockholders, the secretary who keeps track of their schedule, the tech workers who keep their cell phone and e-mail functioning, the janitors who clean their offices, their limo driver, truck drivers and ship captains who transport their oil, writers who do not investigate their human rights violations, engineers and contractors who make the roads that the oil companies’ trucks move on, customers who buy their product, and so on.

Through all these actions they give legitimacy to the oil companies—and prop them up, which allows them to continue with their destructive practises.

A campaign from the 1970s illustrates this. The U.S. government was sending weapons to Pakistani dictator Yahya Khan that were used to murder the people of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). In an attempted genocide, nearly 3 million East Pakistanis were killed.

A group of Quakers in the United States wanted to make a difference. When they found out that some of the arms shipments were loaded from ports in their city, they picked a dramatic action to stop the flow of weapons –– a naval blockade! For a month, they publicly practiced “naval maneuvers” in canoes and kayaks in front of TV cameras. Some days had themes—religious leaders, kids, elders—all leading up to the arrival of the gigantic freighter ships bound for Pakistan. (Read more about the theory and tactics of kayaktivism.)

When the first ship arrived, the group jumped into their canoes and paddle boats. The coast guard immediately pulled them out, as photographers tried for the best picture. Over the next weeks, they played ‘a cat-and-mouse game,’ as the freighters tried to avoid the public spotlight by changing their arrival times or rerouting to other nearby ports. But an important group of people was watching the unfolding storyline on TV –– the longshoremen employed to load the ships.

The Quakers went to bars and met with them. The longshoremen were struck by their sincerity and the sense that this was a historic moment. The local longshoremen union agreed to refuse to load weapons headed to Pakistan. It was the beginning of the end.

The local longshoremen convinced the national union to stop loading any military shipments to Pakistan. With that crucial pillar of support removed, the government couldn’t use any port on the East Coast to send arms. This classic civil disobedience made it prohibitively expensive to send the weapons. Soon after, the federal government announced it would no longer support the dictator (unsurprisingly, they did not mention the activists’ role).

Without firing a shot or making a single lobby visit, this small group forced the hand of the the U.S. empire. That’s power.

This is a different view of “people power” than people merely working together to try to persuade powerholders to change. Instead it uses the specific strategy of conversion of allies to destabilise power. By analyzing our targets using this way of viewing power, we may see new pillars we can “remove” from the system—and also better analyze who power sources we have relationships and access to in order to force change. (Read more about Power-Mapping your target.)

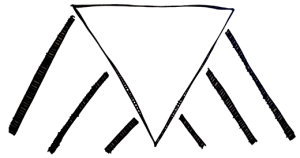

Pillars of Support

Use this to analyse the power of your campaign target.

- Start by putting your target in the center.

- Brainstorm different pillars of support. Who gives support to that target? Even if they disagree with them (or don’t care about their position), who are the people who carry out the orders or otherwise hold up that pillar? Be specific with the names of unions, media conglomerates, secretaries, and so on.

- If necessary, you may want to take some of those and make them into separate upside-down triangles with their own pillars of support.